In this blog-post, I want to share my experience in the field of science communication and give

you my personal perspective of things.

I would be very happy to receive your feedback. Maybe, you disagree with what I say? Maybe, I missed something in my discussion? Feel free to contact me (t.beuchert@uva.nl) or post a comment below.

Who we should communicate with and why

“Science communication” is a term that one can write a lot about. I think what is important is that we would like to bridge between the broad public and the scientific community as well as within the scientific community itself. That way, we can establish links that are naturally missing due to a community that is specialized in more and more distinct niches.

When accomplishing our degrees in sciences, we do not only earn dignity but also the responsibility for making the achievements of humankind accessible to humankind. Secondly, a vivid, critical, and lucid exchange between fellow scientists is absolutely necessary to maintain and continuously improve on the quality of our research. While the former is actively pushed forward (media, public events, etc.), communication within the scientific environment is still underrepresented. How can it be that biologists and astrophysicists share common walls but don’t talk to each other? What about joint seminars every few months involving all groups and departments? I do also want to mention our role in politics and public life. Often, the power of words and phrases are (ab)used to form and/or steer opinions. There is a broad set of political parties and pressure groups, all interacting in an opaque web that makes it mostly impossible to stick to true facts or act in the most meaningful way. This of course assumes that the most meaningful thing to do is obvious. I really want to emphasize that despite a lot of dissatisfaction with the way politics and lobbies work, it is not a matter of course that we DO have the right in many countries to take part in shaping politics. I want to emphasize the power of every individual even when being “just” one part of a large number of people. I think that this idea is very dangerous. The very basic requirement for getting involved and sharing our opinion, is to actually form an opinion. Everyone knows, how difficult this can be. How can we as non-experts in a specific field be able to distinguish right from wrong (speaking of hard facts). The WWW has not even existed for a century, but contains literally everything. Everyone has free access to all kind of stuff and one is often confronted with diverging information. Philosophers are able to convince us on one page of being our own grand parents (I urge that this discipline is certainly as justified as natural sciences). How can one tackle these problems of the modern world? One way, I suggest, is that we as researchers have to make absolutely sure to work to the best of our knowledge and in a truthful manner. We have to seek contact outside of our offices, BOTH with ourselves, other disciplines, and the outside world. We have to see it as our life-long responsibility as professional researchers to communicate and discuss, to provide information and intercept whenever needed, and to keep a healthy balance of information and understandability. And last but not least, we have to not loose our passion.

To summarize: we live in a world suffering an inflation of information. Times of omniscience are over. There are specialists everywhere. We became busy beings. How can we still find time to widen our horizon? Youtube channels and TV shows fight for our attention, and beat us with information and nice pictures of the great great

universe. Keeping track of publications in just one field is a challenge. How do we best filter information? How do we process them? I think the responsibility of scientists is higher than ever to provide their service to humankind. We often have the feeling of being insignificant beings drilling tiny and eeendless holes in distinct

problems. While doing so, we loose perspective. We forget that we have learned to quickly grasp complex issues and depict them in simple words. This way of re-digesting information is something highly demanded in society.

For those of you understanding German, I suggest to read a statement by the physicist and scientific journalist Ranga Yogeshwar: https://www.spektrum.de/kolumne/und-was-bringts-mir/1563312 .

Let me provide a few examples that illustrate why I think better communication is necessary. Often, while individual facts are true, the big picture is getting lost, leading to misinterpretations.

- I recently stepped over a Netflix movie called “Cowspiracy”. This movie pretends to unveil the, as it seems from the movie, never considered fact that methane is the killer-gas. Don’t get me wrong. Methane is certainly a well-mixed greenhouse gas and harmful for our climate! Our immense consumption of meat, having large rice fields, etc. lead to an increase of 150% of methane (relative to the year 1750) as opposed to CO2 (“only” 40% increase). In between the lines, the movie seems to relativize CO2 as a driving force, which is not true for what concerns us today. The big plus is that they provide extensive references on their homepage. If you look at those, however, there is a problem. They refer to the “Global Warming Potential” (GWP), which integrates the radiative forcing after a sudden release of a greenhouse gas over time, relative to the integrated value for CO2. The moviemakers mention that after 20 years, methane would be “25-100 times more destructive than CO2” and that it would have a GWP 86 times that of CO2. Their source is the climate report “IPCC”, which, however, is very cautious about how to interprete the GWP. I can recommend a read! The GWP is a nice theoretical value but tells us not a lot about the reality. Even if the GWP is as high as 86 for CH4 – if a cow poops now (even if all cows pooped now), it does not mean that the net radiative forcing will be 86 times as strong in 20 years.

The only measure that makes sense is the actual radiative forcing of a greenhouse gas since, for example, the pre-industrial time. This value tells us that since 1750, CO2 enforced an extra energy flux of ~1.7 W/m2 onto our atmosphere (~1 W/m2 for CH4). The problem is that the movie misses to provide some very important information. The half-life time of methane in our atmosphere is ~12 years vs. hundreds of years residence time of CO2. Also the CO2 concentration is much much higher than CH4.

The only measure that makes sense is the actual radiative forcing of a greenhouse gas since, for example, the pre-industrial time. This value tells us that since 1750, CO2 enforced an extra energy flux of ~1.7 W/m2 onto our atmosphere (~1 W/m2 for CH4). The problem is that the movie misses to provide some very important information. The half-life time of methane in our atmosphere is ~12 years vs. hundreds of years residence time of CO2. Also the CO2 concentration is much much higher than CH4. - During a career day for Physicists in Germany, I once heard a talk by someone, who is now in the private sector but used to work for the automobile industry. This engineer, who should be considered an expert in his field, provided a closing statement that shocked me. The meaning was “forget about electromobility, it doesn’t really help us”. We were all physicists in this room and everyone should have been able to think critically. But hardly anyone did. A few of us had a conversation with him over lunch to explore his motivation behind.

It turned out that his only reference was a popular science article. Going into that one, many issues were not discussed. I consider the argument that producing batteries would be very cost- and C02-emission-intensive quite “short-ranged”. Of course, electromobility is not emission-free when considering everything related. Batteries that are produced in CO2-intensive ways in a few countries only are harmful for our global climate. I fully agree that the term “emission-free” is yet another example for a misleading term (ab?)used by companies and politics. We nevertheless need fair discussions, and consider both sides of the medal. We need to think of far-reaching aspects. Technologies are being developed. The CO2 concentration and its sources are not uniformly distributed – electromobility can help to relieve polluted areas. The technology may improve the efficiency of batteries over time. Certain countries are able to produce energy used for the production of batteries from renewable energy supplies. Smart grids and machine learning techniques can help to increase the efficiency of the entire system and may eventually lead to negative greenhouse-gas emission.

It turned out that his only reference was a popular science article. Going into that one, many issues were not discussed. I consider the argument that producing batteries would be very cost- and C02-emission-intensive quite “short-ranged”. Of course, electromobility is not emission-free when considering everything related. Batteries that are produced in CO2-intensive ways in a few countries only are harmful for our global climate. I fully agree that the term “emission-free” is yet another example for a misleading term (ab?)used by companies and politics. We nevertheless need fair discussions, and consider both sides of the medal. We need to think of far-reaching aspects. Technologies are being developed. The CO2 concentration and its sources are not uniformly distributed – electromobility can help to relieve polluted areas. The technology may improve the efficiency of batteries over time. Certain countries are able to produce energy used for the production of batteries from renewable energy supplies. Smart grids and machine learning techniques can help to increase the efficiency of the entire system and may eventually lead to negative greenhouse-gas emission. - I have often been asked, why astrophysicists spend so much money in new technologies and space exploration. This money could also be spent to fight poverty. Let me first give you my personal view, before I compare numbers.

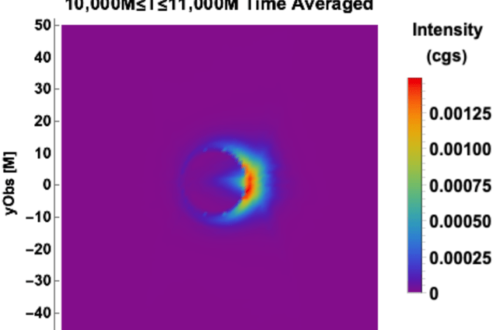

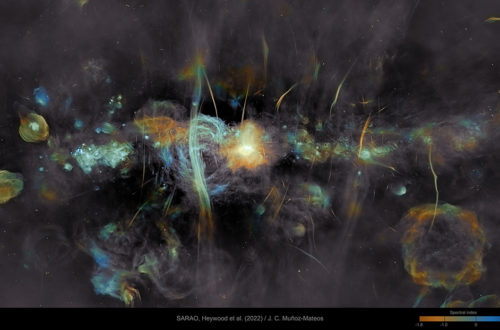

HOTAKA SHIOKAWA/CFA/HARVARD Of course, it has to be in the interest of everyone to fight poverty and the serious deficits we are facing in the world. In my eyes, however, it is also a deeply rooted desire of humankind, to ask and seek for answers. We would like to know about our origin, our future, and our neighborhood. It is as justified as us performing, creating and enjoying arts. It is and has always been part of our nature to understand nature, to express, and reflect ourselves. We for example know that there are black holes out there (see also the blog post on “Predicting what black holes look like” by Sera Markoff). With black holes acting as central engine, we observe matter being accelerated over incredible distances with velocities close to the speed of light (see also the posts by Atul Chhotray, Gibwa Musoke, Dimitris Kantzas, Thomas Russell, Koushik Chatterjee, Felicia Krauss, Casper Hesp, and myself). We see other stars forming and dying. I think it is just healthy curiosity to explore these fascinating phenomena. Although I could stop here, I want to raise one more point. During days, where the climate change is more and more seen as a global threat, we start to step back from our comfort zone and see in Earth more than just the street that we walk on every day, or the beautiful coast that we may see during our vacation. We see Earth as our home planet – a planet that spins around its axis and orbits our sun, yet causing weather and climate. A fragile system. By the way, I experienced that not many do know about this and why there are seasons. Again a challenge to us as researchers but also schools. Anyway. Our fragile Earth is protected by a fragile atmosphere that seems very thin when seen from orbit. Fundamental research does not only answer philosophical questions. It can help us survive. Migrating to other planets is not an option – not on timescales that matter for us right now. The whole universe out there is a hostile environment. And we are about to grow a hostile environment on Earth as well by accelerating or counteracting natural trends, triggering climate feedback mechanisms that we have no control of, etc.. We only have our home. Science and research are inevitable to understand our home better and to help us to protect ourselves against our own influence. Now about numbers. A mid-class ESA science mission costs around 500 Million Euros. Usually it takes tens of years until a mission is launched to study our Earth or the universe. Also, each member state contributes to ESA. Its budget for 2018 is 5.6 Billion Euros. As I still have it in mind: in Germany each citizen contributes approximately with a cinema ticket per year. For comparison, the defense budget in Germany was 37 Billion Euros only for 2017. The budget of the European defense union was about 230 Billion Euros (2016) for comparison. I am not intending to start a political discussion. I am also not implying that financing the defense sector is driving poverty. Part of their actions are also related to peace-keeping and crisis solving. The underlying cause and origin for global conflicts is a whole different story. I am just more or less naively providing numbers here, which of course also can’t be compared 1:1, but shall give you a feeling for the orders of magnitude.

What are the tools of science communication?

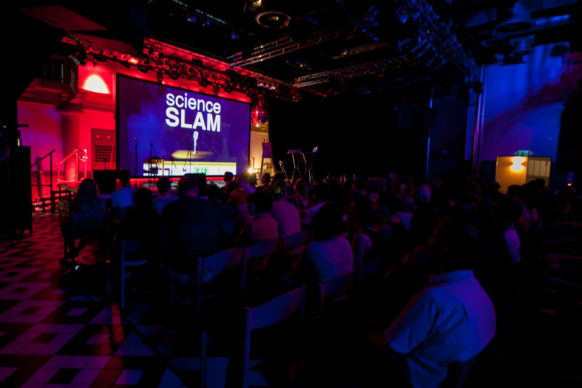

There are many tools. Things that any scientist can do is to write blogs, have conversations, publish articles, also in popular science magazines, participate in one of the numerous events like “FameLab”, “Science-Slam”, “Nerd Night”, “Astronomy on Tap” and many more. Some also do science communication for a living: a friend of mine for example researches on this topic, which will eventually improve on the methods. He also acted as a moderator between companies and citizens when it comes to decide on the construction of windmills. It was his merit to have a purposeful discussion based on unbiased facts.

I can report on Science-Slams, where I participated a couple of times. This format was born in Germany and expanded quickly. Scientists with an active research topic present their field in ten minutes following the slogan “prodesse et delectare” (“utilize and please”). The audience is usually well mixed both in age and profession. Also, we as the performers and scientists can learn a lot from each other. It happened several times that ideas and methods mentioned in one field, were picked up by another field. A story I tend to tell often happened one evening. A few colleagues and I gave science slams for the opening of the “long night of sciences” in my home town. A colleague did some research on the statistics on new-born babies in hospitals. The graph (number of babies vs. weight) showed strange, distinct peaks. How come? It turns out that hospitals receive extra money for babies that weight not enough and are thus more vulnerable. And as it was an official event, the director of the gynecological hospital was also in the audience, eventually offering my colleague a job as lecturer. 🙂

The only measure that makes sense is the actual radiative forcing of a greenhouse gas since, for example, the pre-industrial time. This value tells us that since 1750, CO2 enforced an extra energy flux of ~1.7 W/m2 onto our atmosphere (~1 W/m2 for CH4). The problem is that the movie misses to provide some very important information. The half-life time of methane in our atmosphere is ~12 years vs. hundreds of years residence time of CO2. Also the CO2 concentration is much much higher than CH4.

The only measure that makes sense is the actual radiative forcing of a greenhouse gas since, for example, the pre-industrial time. This value tells us that since 1750, CO2 enforced an extra energy flux of ~1.7 W/m2 onto our atmosphere (~1 W/m2 for CH4). The problem is that the movie misses to provide some very important information. The half-life time of methane in our atmosphere is ~12 years vs. hundreds of years residence time of CO2. Also the CO2 concentration is much much higher than CH4. It turned out that his only reference was a popular science article. Going into that one, many issues were not discussed. I consider the argument that producing batteries would be very cost- and C02-emission-intensive quite “short-ranged”. Of course, electromobility is not emission-free when considering everything related. Batteries that are produced in CO2-intensive ways in a few countries only are harmful for our global climate. I fully agree that the term “emission-free” is yet another example for a misleading term (ab?)used by companies and politics. We nevertheless need fair discussions, and consider both sides of the medal. We need to think of far-reaching aspects. Technologies are being developed. The CO2 concentration and its sources are not uniformly distributed – electromobility can help to relieve polluted areas. The technology may improve the efficiency of batteries over time. Certain countries are able to produce energy used for the production of batteries from renewable energy supplies. Smart grids and machine learning techniques can help to increase the efficiency of the entire system and may eventually lead to negative greenhouse-gas emission.

It turned out that his only reference was a popular science article. Going into that one, many issues were not discussed. I consider the argument that producing batteries would be very cost- and C02-emission-intensive quite “short-ranged”. Of course, electromobility is not emission-free when considering everything related. Batteries that are produced in CO2-intensive ways in a few countries only are harmful for our global climate. I fully agree that the term “emission-free” is yet another example for a misleading term (ab?)used by companies and politics. We nevertheless need fair discussions, and consider both sides of the medal. We need to think of far-reaching aspects. Technologies are being developed. The CO2 concentration and its sources are not uniformly distributed – electromobility can help to relieve polluted areas. The technology may improve the efficiency of batteries over time. Certain countries are able to produce energy used for the production of batteries from renewable energy supplies. Smart grids and machine learning techniques can help to increase the efficiency of the entire system and may eventually lead to negative greenhouse-gas emission.