Our ancestors have been monitoring the night sky since 5000 years ago, making astronomy the oldest natural science. Most stars seen on the night sky have been there for millions to billions of years, except that they rise and descend along with the Earth’s rotation. But if one is very patient and lucky, one could see that the sky is changing. For astrological purposes and other reasons, the variation of the sky had been recorded by ancient astronomers. In addition to the comets and meteors, many transient events occur outside of our Solar systems. The astronomical term “transient” expresses the phenomena that some celestial objects switch on and off their lights as observed on the Earth. Now modern astronomers have already known that many objects show transient behaviors, such as novae, supernovae, pulsars, and some binaries. However, transients must surprise ancient people as they did not understand why the stars are changing. In both the eastern and western countries, ancient astronomers considered these changing “stars” to carry omen from the sky. The records of them provide the earliest measurements of the transients and the best evidence that our ancestors had good monitoring systems for stars.

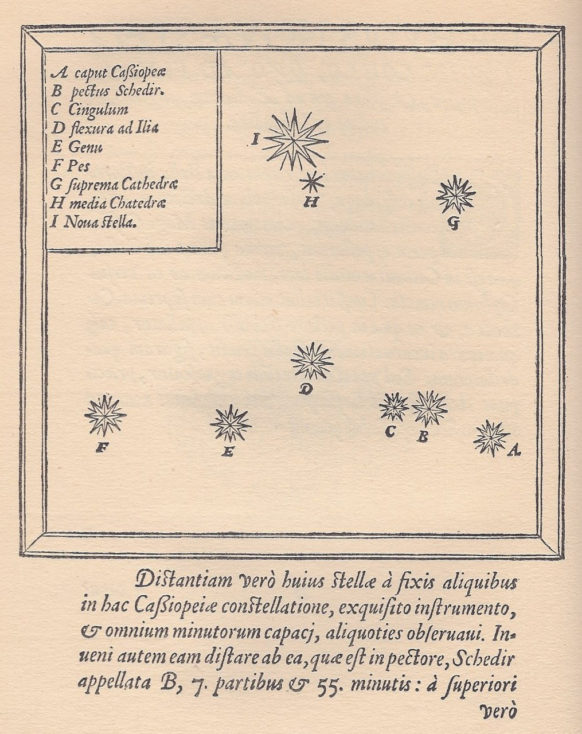

One of the most recent historical transients was Tycho’s supernova, which was sighted on November 11, 1572, and recorded as “Novae Stella” by the famous Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (Figure 1). Supernovae are among the most energetic explosions in our Universe, originating from the deaths of the massive stars or white dwarfs. What we observe today at the position of Tycho’s supernova is a beautiful expanding nebula. The ancient records by Tycho Brahe provide vital information about the light evolution of supernova. By comparing them with the modern supernova observations, we learned what kind of explosion it was (Type Ia) and what the progenitor star could be (white dwarf). Another important impact of Tycho’s discovery is that people began to reconsider the influential Western philosophy that the sky is unchanging as described in Aristotle’s Universe.

In the far East and in Arab, the variation of the sky has been monitored since much earlier time. Most records of the transients in the first millennium and before the common era are found in ancient Chinese texts since the ancient Chinese astronomical bureau had systematically monitored the sky. The transients with fixed positions on the sky were usually called “guest stars”, with the meaning that they are not the host stars but visitors staying for a short period of time. According to the catalog compiled by Xi & Bo (1965, Acta Astronomica Sinica, 13, 1), around 100 supernovae-like or novae-like transients had been recorded from the 14th-century BC (oracle bone inscriptions) to the 18th century. A few of them correspond to supernova remnants seen in today’s sky, such as Kepler’s supernova (1604 CE), Tycho’s supernova (1572 CE), the Crab Nebula (1054 CE), SN1006, RX J1713.7-3946 (393 CE), RCW 86 (185 CE). Last year, we added a new association by suggesting that a young supernova remnant called G7.7-3.7 originated from a guest star sighted in “Nan-dou” asterism in 386 CE (see Figure 2, Zhou et al. 2018, ApJL, 865, 6).

Historical supernovae only contribute a few fractions of transients in ancient records. What about the origin of other transients? Some of them could be novae, which are eruptions from binary star systems containing white dwarfs. These events happen more frequently than supernovae, as supernovae are rare events with an occurrence of 2 or 3 per century in our Galaxy (most of them are too faint to be seen on the Earth with the naked eye due to the high extinction across the Galactic plane). Unfortunately, so far only very limited guest stars have been identified as novae (e.g. Shara et al. 2017, Nature, 548, 558). Moreover, a transient sighted in 1408 CE was suggested to be related to the black-hole binary Cygnus X-1 (Li 1979, Chinese astronomy, 315, 17), but the possibility is highly uncertain (Stephenson & Green 2005, Journal for the History of Astronomy, 36, 217). It is not an easy task to link historical transients and the objects in the current sky. It is still an enigma what the remaining transients are.

Last month, we organized a workshop on historical transients at the Lorentz Center at Leiden (see Figure 3). Astronomers and a few historians and philosophers gathered together to discuss what we can advance and what we need. Despite many achievements in the past century, there are still many questions unanswered and many mysteries to be uncovered for historical transients. There is no doubt that historical texts carry important scientific values for modern astronomical studies of transients, but it is also crucial to have a proper understanding of the historical texts. The study of historical transients need efforts from both astronomers and historians. As an astronomer, I feel very excited to be able to study ancient transients. It is fun to use the astronomical data taken over a thousand years ago, and in this way, we are actually able to make millennial collaborations with ancient astronomers.