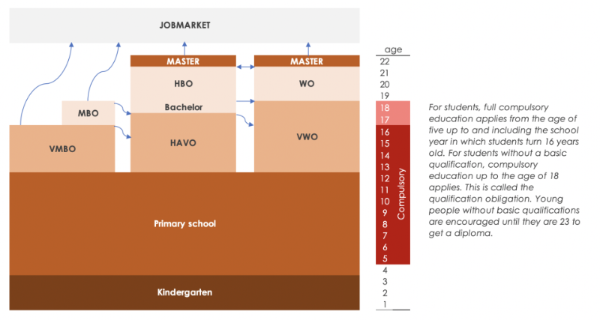

As discussed in Part I, I think it’s very important to teach children about science and what it’s like to be a scientist. It’s more important that we teach children invaluable skills such as being curious, critical thinking and creativity than that they secure high grades in school. In an ideal world, every child is introduced to science and is allowed to discover whether they like to do science. Unfortunately, the Dutch school system has some issues regarding this and there is still the need for initiatives like the Altair project. Let us take a look at the Dutch school system and what can be done. Before delving into this, an overview of the system is given in the figure (below), together with the corresponding ages of children on the right. More information can be found here: [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Education_in_the_Netherlands]

In Dutch primary schools the focus is mostly on learning Dutch and arithmetic. Dutch children don’t really encounter science at primary school except for a little bit of biology. Nowadays, many schools try to set up science projects but that’s really up to the school and usually depends on how much money they have available. If this is not the case, science is practically absent and the teaching is pretty old-fashioned. In the last year of primary school, children do a national test called ‘CITO’. The results of this test together with the advice of the teacher will determine what level the child will do in secondary school.

The system makes young children change their direction all the time. In the final year of primary school, at the age of 12, they have to choose between the university track (VWO) or schools more focused on professional training (HAVO and VMBO). Then, in the second or third year of secondary school they have to change course again and choose between different profiles. Here they can choose a profile more aligned with natural sciences or more aligned with social sciences and arts. All these “choices” are based on scores and grades combined with the advice from teachers. This obviously allows various forms of bias to creep in throughout the child’s school career. Ultimately, children from wealthy families gain better opportunities through additional training and tutoring to secure higher grades. Moreover, Dutch families, especially those with well-educated parents, possess a clear advantage due to their familiarity with the system. This disparity is reflected in society, where these individuals, often white males, dominate prominent positions in industry and science. Unfortunately, this skewed representation is not a correct reflection of Dutch society.

This is very different compared to the US school system where children choose much later. In the US system children do have choices but they all have the same core curriculum in high school. Once they decide to go to university, they have a 4 year BSc in the liberal arts tradition, and take 1-2 years of classes before they have to pick a major. I think, it’s there that we see another problem with the Dutch school system arising. How can children ever find out whether they like doing science or anything else when constantly being forced to choose and perform? Putting children under pressure is not inherently bad, but the focus should be on developing the right qualities rather than solely on obtaining high grades.

As an alternative, there are people thinking about introducing something similar to ‘middle school’ in the Netherlands. The idea is that children who finish primary school go to this middle school for 2 years when they’re 12-14 years old. During this middle school, they will do a very general set of subjects and they can discover what they like. There is no difference in difficulty level and the children can adjust to a different school system. This idea seems great but there is much discussion in the country and no one really wants to take the first step to set this up. There are also other solutions but any of these require the system to change significantly and will take a number of years. In the meantime, it’s important that we have projects such as the Altair project that still introduce children to science before they go to secondary school. It can give them the small push they need to actually start discovering the world.