noun: imposter syndrome

- the persistent inability to believe that one’s success is deserved or has been legitimately achieved as a result of one’s own efforts or skills.

Unfortunately, the feeling of being a fraud merely skating by on luck is all too common in STEM fields. Women, under-represented minorities, and those early in their careers are particularly susceptible and therefore make up a disproportionate number of “imposter syndrome” sufferers. As a community, there’s a lot of discourse about imposter syndrome and overcoming it on an individual level. But many of the suggested courses of action to combat these internalized feelings of fraud, such as “celebrate your successes” or “let go of perfectionism”, can read as empty platitudes that are typically much easier said than done. Crucially, these suggestions, although well-intentioned, focus more on what individuals can do personally to change themselves, while failing to truly target the pervasive roots of the imposter syndrome phenomenon: feeling isolated or unwelcome in one’s field.

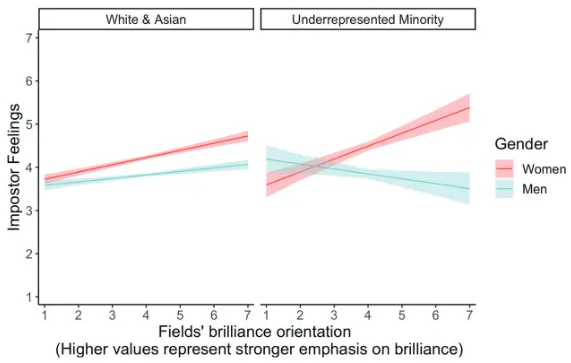

Stronger “imposter” feelings have indeed been linked to a lower perceived sense of belonging in STEM fields [1]. This is particularly pervasive in fields like math or physics where innate talent is implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) considered a prerequisite [2]. For example, women are more likely to experience imposter syndrome relative to men in fields where success and renown are traditionally associated with “brilliance” [1]. This in turn has farther reaching consequences as these biases are implicitly passed on: across the humanities, social sciences, and STEM fields, the perceived requirement of innate aptitude in a field has a distinct impact on the number of URM and female students that complete PhD programs, and thus is a strong predictor of the representation of the women and minorities in those fields [2].

These feelings of otherness within one’s chosen field are of course exacerbated where identities such as gender, ethnicity, and neurodiversity overlap. For example, ADHD and autism have historically been thought to only affect boys and men, with diagnostic criteria being heavily based on male presentation [3]. While this is slowly changing, this means that women are often undiagnosed and dismissed when seeking assessment, leaving them to struggle without the same level of support afforded to their male peers [3]. This can lead to neurodivergent women feeling a compounded sense of self-doubt and insecurity due to the intersection of neurological differences and gender disparity. In another example, women belonging to under-represented minorities report higher rates of imposter syndrome feelings in STEM fields than either white women or under-represented men [1]. This underscores that intersectionality is a necessary and important aspect in the study and combating of imposter syndrome as a systemic effect.

In the end, maybe the “diagnosis” of imposter syndrome isn’t actually all that helpful to people who suffer from it. Beyond packaging a complex range of emotions into a convenient box, what does the term provide? In fact, this neat packaging makes it easy to lay the burden of fixing the result of underlying systemic issues on the shoulders of an individual. After all, isn’t the feeling of having tricked your way into success a natural reaction to the constant bombardment of implicit messaging that you don’t belong? Instead, the path to truly overcoming imposter syndrome lies not in well-meaning but ultimately empty platitudes, but in tackling the systems that give rise to it. By fostering diverse academic environments and combating underlying internal biases, we may be able to put imposter syndrome to rest for good.

References

[1] Muradoglu, Melis, et al. “Women—particularly Underrepresented Minority Women—and Early-career Academics Feel Like Impostors in Fields That Value Brilliance.” Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 114, no. 5, Aug. 2021, pp. 1086–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000669.

[2] Leslie, Sarah-Jane, et al. “Expectations of Brilliance Underlie Gender Distributions Across Academic Disciplines.” Science, vol. 347, no. 6219, Jan. 2015, pp. 262–65. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261375.

[3] Craddock, Emma. “Being a Woman Is 100% Significant to My Experiences of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism: Exploring the Gendered Implications of an Adulthood Combined Autism and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Diagnosis.” Qualitative Health Research, vol. 34, no. 14, July 2024, pp. 1442–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323241253412.