This month, I decided to write a blog post targeted at people outside of astronomy, to explain the reasoning behind one of the tools that we use. This is because I think the means and methods we have for exploring astrophysical phenomena are often as cool as the actual sources that we study, but often we don’t talk about how we go about discovering something. So, in this line, I’m starting simply, explaining the reasoning behind why we use a particular units system.

Now, the title might be the first you’re hearing about this. And you might ask why we would ever, ever choose to measure the largest known things in the universe…in centimeters. And well…it’s partially for historical reasons (an easy way out, but see our determination to stick with magnitudes) but there is actually some reasoning that we can follow.

First of all, this “unit” system is called “CGS”, which stands for centimeters-grams-seconds. It brings in two additional values that seem ridiculous to measure things that live for millions of years, or are hundreds to millions times as massive as our Sun. It sits at odds with the international system of units (SI), which uses primarily meter-kilogram-second. Not that SI sounds much better at tackling astrophysical scales – but we need to keep units of measurement semi-relatable to our lives, so that some portion of these physical and astrophysical phenomena are in a language we can understand. For instance, blue whales are definitely a lot bigger than a centimeter or a meter, but are they really a useful measurement? (That would be approximately 5,036,427,996.9 blue whales between the Sun and Earth.)

So why do we use CGS, instead of the world standard SI?

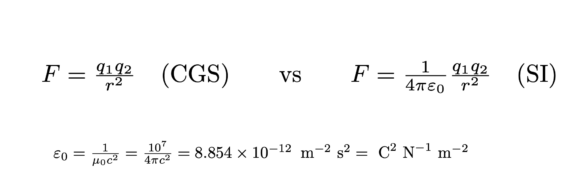

The most compelling reason is the fact that it simplifies equations we use to describe electromagnetic phenomena (e.g. charge, current, voltage). Specifically, it simplifies Maxwell’s Equations which form our foundation of classical electromagnetism (Figure 1). In SI units, these equations have two additional constants: the permittivity and permeability of free space: ε0 and μ0. This is an example of how Coulomb’s law (the force between two charged particles (q1, q2) at some distance r) differs between the CGS description and SI:

To simplify matters, using CGS means that we have less factors to take into account and cluttering up equations, and less hassle when working through calculations. For other units between SI and CGS, it’s not that unreasonable of a difference: just a matter of scaling: moving between increments of length, energy, pressure, masses is all factors, of course: 103 centimeters = 10 meters).

For the record, it’s not only non-astronomers who have problems with CGS – when it was presented to my fellow students and I in our introductory astronomy courses in undergrad, my entire class couldn’t bear the thought of leaving SI for something so ridiculous. Further, if you’re not always utilizing or implementing the values themselves, it’s pretty difficult to intuitively remember that the Sun is actually ~1030 kilograms and not a measly ~1030 grams. In that case, we’d be underestimating its mass by 1000, making it approximately as massive as Jupiter (1.8 x 1027 kg). Intuition isn’t as easy to come by when the number has many many zeros in it. (In CGS, the correct value for the Sun is ~1033 grams).

For a closing fun fact about astronomy, if you remember before how I mentioned that it’s important to us to use unit systems we’re familiar with (sorry, whale!) – the solar system and our Sun become our familiar units when we try to measure the rest of the universe. For example, we use solar masses (1 solar mass = 1.989 x 1033 g) to measure everything from brown dwarfs to massive stars, to supermassive black holes (Sgr A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy, weighs approximately 4 million solar masses, or 1039 grams!)

P.S. If you’re really interested in other astronomy “how” methods, the science communication channel 3Blue1Brown made an amazing two-part series on how, over the history of astronomy, we started learning how to measure planetary and cosmic distances. (Title: Terence Tao on how we measure the cosmos | The Distance Ladder Part 1)